Introduction

Most geotechnical engineers and other practitioners in the geotechnical community will be aware of the second generation of Eurocode 7. Parts 1 and 2 of this three-part document have now been published, with part 3 due for publication in April 2025.

One aspect of the new code is the promotion of the use of ground models as part of the geotechnical design process. Whilst there is nothing new about ground models, (indeed practitioners have been using them for several decades in the UK), their elevation to being a requisite part of the design process is new.

This article describes the purpose and process for constructing a ground model in accordance with the requirements of EC7 and mirrors a presentation given by the author at the recent EC7 seminar in Paris. Much of the content of this article also forms part of a much more detailed paper written by Eurocode 7 Task Group C2 to support EC7 Part 2 in relation to the use of ground models. This more detailed paper is titled ‘Assembling the Ground Model and the derived values’ and will be published by the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission.

What is a Ground Model?

EC7 Part 1: Clause 3.1.6.6 gives the following definition: Ground Model is a site-specific outline of the disposition and character of the ground and groundwater based on results from ground investigations and other available data.

EC7 Part 2: 4.1, further states that: A Ground Model shall comprise the geological, hydrogeological, and geotechnical conditions at the site, based on the ground investigation results.

These definitions offer a clear distinction between a Ground Model and a Geological Model.

Fookes (1997) describes a geological model as ‘a representation of the geology of a particular location’

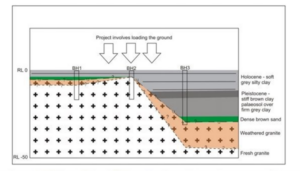

Figure 1: Simple Geological Model Figure 2: Simple Ground Model

Figure 1 shows a simple geological model, that could be constructed by reference to geological maps and other desk study data. This model however provides no information on groundwater, structural loadings or the geotechnical units. In contrast, Figure 2 illustrates a simple ground model that includes all these key factors that will influence design.

In attempting to find a Ground Model that all European colleagues could agree on, the task group decided not to follow the work of the International Association of Engineering Geologists (IAEG) commission 25 publication No. 1: Guidelines for the development and application of engineering geological models on projects. IAEG developed the concept of ‘An Engineering Geological Model’ (EGM). This is defined as ‘the interpretation and assessment of the engineering geological conditions and allows the interaction of these conditions with the proposed project to be evaluated, so that appropriate engineering decisions can be made.’

With the EC7 Ground Model being linked to a specific structure / structures, its construction as proposed by TG C2 is subtly different.

What is the purpose of the GM?

The Ground Model is a verbal/graphical/schematic tool and is a process that is used to advance knowledge of the ground and groundwater characteristics within the zone of influence of the structure (or structures) and to help identify the corresponding risks.

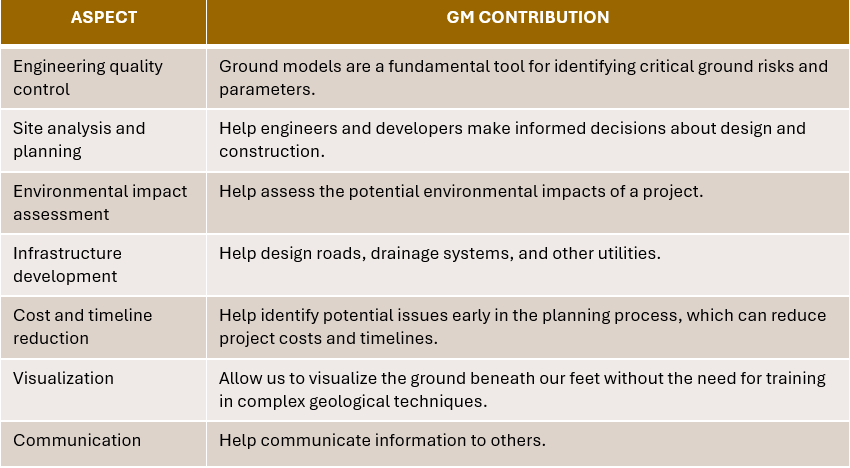

Ground Models must be in a form that can be understood by all geoprofessionals. Any Ground Model must consider the Zone of Influence (ZOI), since they are intrinsically linked, and the ZOI should be defined at the same time as the Ground Model is first considered. The relationship between Ground Model and ZOI is explained and developed as an important concept within EC7 Part2. Table 1 provides the key contributions that the Ground Model makes to the design process.

Table 1: Key contributions of the Ground Model to the design process

To reinforce the purpose and usability, there are some ‘shall’ clauses in Part 2 of EC7.

1. Variability and uncertainty of geological, hydrogeological and geotechnical conditions and properties shall be included in the Ground Model.

2. The detail and the extent of the Ground Model shall be consistent with the Geotechnical Category and the zone of influence.

3. The Ground Model shall be progressively developed and updated based on potential new information.

4. The Ground Model shall reference the derived values of ground properties for encountered geotechnical units.

5. The Ground Model should be documented in the Ground Investigation Report

6. As an alternative to 5, the Ground Model may be documented in the GDR

These clauses set out some important rules for the rationale for and construction of the Ground Model and provide the basis for all Ground Models, regardless of size and complexity.

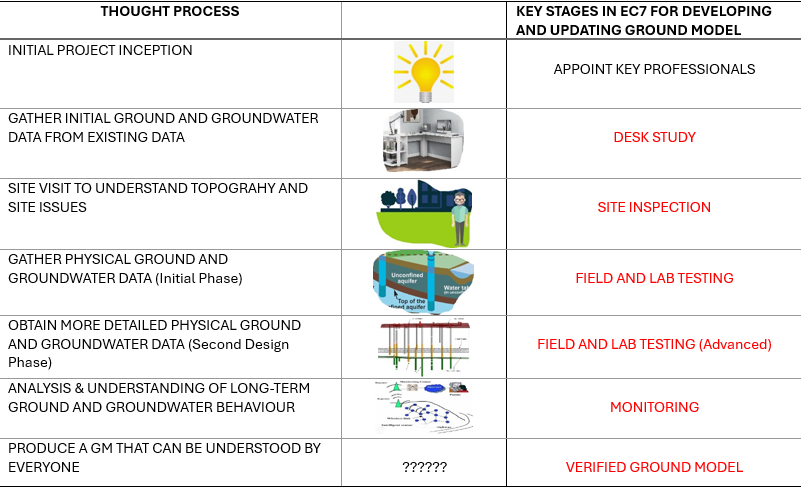

What is the Process of Constructing a Ground Model?

The Ground Model is not a box ticking exercise! The process of constructing a Ground Model forces us to think about the ground & groundwater and how they will interact with the structures we are building.

However simple or complex we decide to make the Ground Model, it must reflect all the potential ground and ground water issues

It is also vital to link the Ground Model to the zone of influence of the structure (or structures) being considered. This is perhaps one of the most important aspects of the process of Ground Model construction, but unfortunately it is often not done and leads to errors / omissions in the data that is captured.

The process of identifying the ZOI must consider all possible impacts and influences of natural features and man-made structures both on the site and surrounding the site. The Ground Model cannot be of a lesser size than the ZOI if all possible influences are to be considered. Guidance on linking the Ground Model to ZOI in the form of examples is given in the paper prepared by Task Group C2 and this will be published shortly as an accompaniment to EC7 Part 2.

Why is the ZOI linking to the Ground Model so important? We need to understand what impact our structure(s) will have on the adjacent ground and on any existing adjacent properties. Dewatering, ground freezing, or the placement of long soil nails, anchors, or rock bolts, etc., that extend into the surrounding ground, could all impact on the ground or adjacent structures.

Similarly, large bodies of water (reservoirs, lakes, etc.), areas of contamination or other hazardous ground, existing structures with deep piled foundations adjacent to our site, may impact the site, insofar as the existing pile group ZOI may overlap with that of the proposed structures. Similarly, activities with cyclic loadings may have to be considered if they would impact the proposed structures.

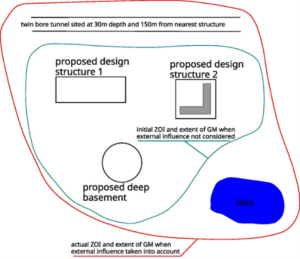

Figure 3 shows an example of how an initial estimation of zone of influence (blue line), fails to take into account all the possible site constraints relating to existing structures both manmade and natural, that are present on surrounding land, (red line).

Figure 3: Relationship of the Zone of Influence to proposed structures

Table 2: Typical thought process for the construction of a ground model

Input bases for the Ground Model

Inputs for the Ground Model will be acquired over a period of time, because the model is ‘live’ throughout the construction process and is all about data acquisition. This period will depend on the complexity of both the ground and groundwater conditions within the area under consideration, and the construction itself.

Within each key input stage, the Ground Model should be formed of both the known and anticipated geological, geomechanical, hydrogeological and geotechnical conditions at, under, and around the site, i.e., in the Zone of Influence. As noted previously the ZOI should be ascertained at an early stage during the life of the project but may change in scope as proposals for structure(s) are refined/changed. It is stressed that an accurate understanding of the ZOI is key to ensuring that all inputs that may be relevant to the Ground Model are considered.

What are the key ‘natural’ input bases?

• Geological conditions including, but not limited to the description of the site geomorphology, the lithology of the geotechnical units, the potential presence and level of a geometrical and physical properties and orientation of discontinuities and weathered zones, the rock mass classification.

• Geomechanical (preliminary assessments of in situ stresses, elastic properties and rock strength?)

• Hydrological conditions address surface, groundwater and piezometric levels, including their potential variations with time and the presence of other fluids or gases affecting the site.

• Geotechnical characteristics of the geotechnical units.

• Seismological assessment for the wider area needs to be undertaken at an early stage

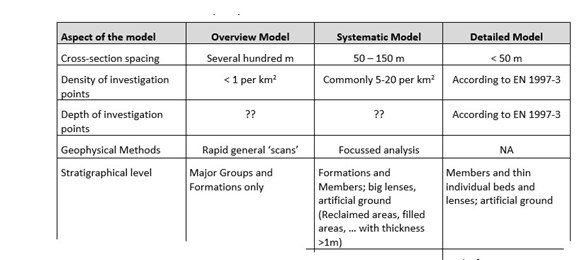

Based on an initial understanding of the ground and groundwater, the project, and the type of construction, some initial assumptions regarding the size and complexity of the Ground Model may be constructed. Three levels of complexity may be considered: general/overview, systematic and detailed. These will help inform the type and quantity of input parameters for the Ground Model. Table 3 provides an extract of a more detailed table contained with the JRC supporting document, that provides such guidance.

Table 3: Extract from a table on guidance on inputs for different scales of Ground Model

It should be noted that one or more types of Ground Model may be required. It may be necessary for example to have a general ‘overview’ model for the project, as well as one or more systematic / detailed models to illustrate different structures or parts of structures. Such requirements are likely to become clear as the project proceeds.

The guidance paper provides input considerations for each stage.

It is important to recognise that there are other non-geological and groundwater related inputs that may need to be considered. These include but not limited to:

• Historical use of ground

• Existing structures / remaining substructures

The historical use of the land is more generally examined as part of the desk study (old historical charts or maps, aerial photography, etc.) to prepare an investigation strategy.

However, the site visit can give vital information and / or clues on the former site use. For example, surface depressions, voids, discoloured soils, artificial soil and rock exposures can all point to human activity on the site, both at surface and possibly at depth

Figure 4: Examples of historic land use

It is common, particularly in urban areas, for new construction projects to take place on sites or areas of land where there has been previous building. Often, such previous structures can be dated within the past 200 years, but there are occasions when much older structures are present.

In all cases careful consideration of available maps and plans should be undertaken to ascertain the likely extent of such structures, both at ground level and also with respect to buried elements of the original buildings.

Figure 5: Historic Buildings beneath site Figure 6: Historic man-made caves beneath site

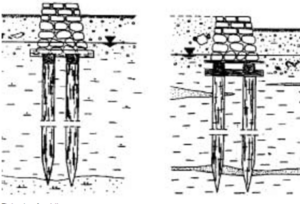

Consideration should be given to hidden infrastructure, e.g., cables, pipes, tunnels, and potential archaeological finds, (see figures 5 and 6). At a more detailed level, having identified that historic structures might impact on the new structures, it may be possible to access foundation records. Old timber piles if not identified, can still present problems for new construction, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7: Historic drawing of timber piles

Once more information regarding the types of structures and their associated foundations is known, more specific inputs for the Ground Model can be considered. In particular, values associated with specific foundation types should be considered as should cases where foundations will interact with adjacent foundations. An example of this is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8A: Structures Figure 8B: ZOI for individual structures

Figure 8: Principle of defining the zone of influence according to the type of structure

Conclusions

The formalisation of the requirement to produce a Ground Model as part of every ground investigation is a key element of the redrafted Eurocode 7. It has been recognised as the best method of documenting all the known ground and groundwater information that is gathered during the life of a project. The main ‘takeaways’ from the whole process of Ground Model construction are:

• Ground Model process can be as simple / or as complicated as you want!

• It is vital to consider the Zone of Influence!!

• It is not meant to be an onerous task

• BUT.. If process of constructing the Ground Model is done properly, you will identify potential risks

• You will help to eliminate unwanted surprises in the design process

• A good Ground Model provides an excellent method of disseminating data to all geoprofessionals

The full paper that will be published by the European Commission’s JRC will provide more in-depth guidance on assembling the Ground Model and it is recommended that this should be read in conjunction with Eurocode 7 part 2.

References

BS EN 1997‑1:2024 Eurocode 7 — Geotechnical design Part 1: General rules

BS EN 1997‑2:2024 Eurocode 7 — Geotechnical design Part 2: Ground properties

Fookes, P.G. (1997). Geology for Engineers: The Geological Model, Prediction and Performance. Quarterly Journal of Engineering Geology and Hydrogeology. Volume 30.

De.Freitas, M.H (2021). Future development of Ground Models. Quarterly Journal of Engineering Geology and Hydrogeology. Volume 54.

International Association of Engineering Geology and the Environment (IAEG), IAEG commission 25 Publication No. 1 2022.” Guidelines for the development and application of engineering geological models on projects.

Nottingham City Council Archives. Historic maps. A map of the Mansfield Road caves (undated).

Przewłócki, Jarosław & Dardzinska, I & Swinianski, J. (2005). Review of historical buildings’ foundations. Géotechnique. 55. 363-372. 10.1680/geot.55.5.363.66017.

Further information is also available from the AGS via the following link:

Bitesize Guide – EC7 Next Generation 01 – Geotechnical Unit, Ground Models and Geotechnical Design Models – what are these, what do they cover and who is responsible?

Article provided by Matthew Baldwin