Marking the second year of gathering accident and incident data from across the geotechnical & geoenvironmental industry, there has been a 127% increase in organisations providing information to the AGS. This perhaps highlights the benefit which has been demonstrated through sharing accident and incident data, allowing industry performance to be communicated, and improvement targets, aims, and objectives set by contractors, as well as the industry body.

Moving forward I would like to think we, as an industry, can build on this improved engagement year on year, prompting more openness across the industry and collectively striving for continued improvement in health, safety and wellbeing. This improvement would form a reliable indicator of an industry with a maturing safety culture.

2023 Accident Incident Data

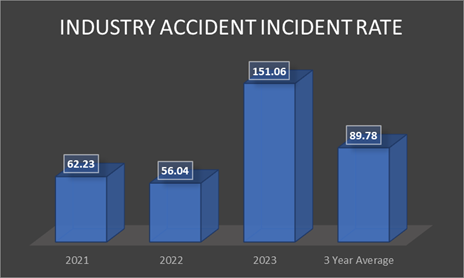

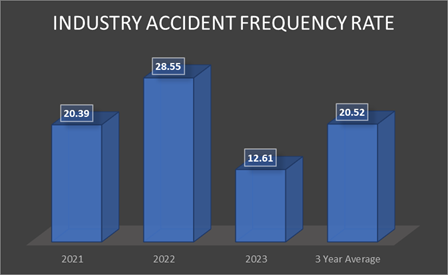

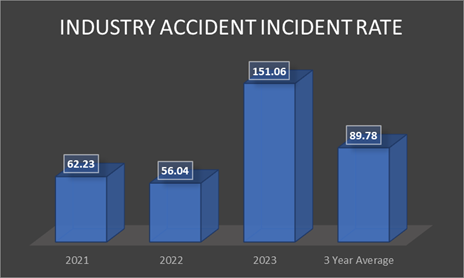

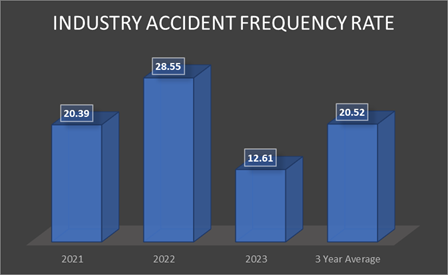

Applying Health and Safety Executive (HSE) frequency and incident rate formulae to allow benchmarking against the HSE Statistics, and maintaining industry uniformity from the data published last year, two accident incident rates have been used to calculate the 2023 data;

- Accident Incident Rate (AIR) – (number of RIDDOR reportable accidents / average workforce headcount) x 100,000.

- Accident Frequency Rate (AFR) – (total number of harm accidents / total number of hours worked) x 1,000,000.

The most obvious statistic in the data is a 169% increase in accidents per head count from the 2022 AIR and a 142% increase from the 2021 AIR. This is a significant shift, highlighting that if you worked within the geotechnical & geoenvironmental industry in 2023, you were 2.5 times more likely, than in either of the preceding years, to experience an injury that is reportable to the HSE. i.e. An injury that would result in you not being able to work for seven days, being hospitalised for twenty-four hours, involving a broken bone, loss of sight, etc.

Examining the 2023 AFR in comparison with the 2022 AFR, the rate has been reduced significantly, down 55%. In isolation this could be considered good news, however viewed together with the increase in the AIR, the message from the data is clear.

‘The industry had fewer accidents in 2023, however the number of persons who were seriously harmed increased significantly’.

Why is this? Considering the data holistically, there are several possibilities, although certainty can only be achieved through detailed investigation of information which extends past that information issued to the AGS.

Weakness in accident reporting culture – Where there is a poor accident and incident reporting culture, minor injuries, near misses and hazard reporting reduce, but more serious accidents, due to workers not being able to continue to work or require first aid, are reported. There are several reasons why this type of weak reporting culture can develop, including poor organisational safety culture, working within environments where accident and incidents are linked to blame, an incorrect assumption that accident incident reporting is a negative (not a learning / improvement opportunity), counterproductive zero accident targets, etc.

Risk reduction prioritisation – The significant hazards within the industry are well established, namely contact with underground and overhead utilities (contact with electricity accounted for 6% of all construction fatalities in 2023), plant people interface (struck by moving machinery & plant accounted for 20% of construction related fatalities in 2023) and manual handling (musculoskeletal disorders make up 54% of all construction work ill health in the three years from 2021 to 2023).

The accident data shift could highlight that hazard identification and correction has focused on easy to target items, such as housekeeping, access and egress, welfare, etc. While this has driven down minor accidents it has allowed more significant hazards to go unchecked, resulting in significant harm.

Economic pressure – 2023 was a tough year for the UK economy, increasing the cost of living significantly. Businesses were impacted by higher energy costs, which also increased the cost of materials. At the same time the workforce, pushed for pay rises or more work to counteract the impact of the cost-of-living crisis.

With this economic strain, it is easy to imagine direct and indirect pressure placed on the workforce to be more efficient, find ways of doing things faster and cheaper, work longer hours increasing fatigue, machinery servicing or repairs being stretched or extended, etc. all which could contribute to an increase in accidents. Although not limited to significant accidents.

The Construction Industry

In comparison to the wider construction industry, non-fatal RIDDOR reportable injures did not increase from those figures prior to the coronavirus pandemic, the rate of self-reported non-fatal injury to workers showed a downward trend in this period. The rate for the latest period, which includes years affected by the coronavirus pandemic, was not statistically significantly different from the 2014/15-2016/17 period.

Accident Incident Data Breakdown

When the data is broken down into organisation size, it highlights that from the small (1 to 10 employees) to the very large (1000+ employees) organisations, the increased AIR is not universal, with the small, large (101 to 1000 employees), and very large organisations maintaining, even reducing their AIR through 2023.

However, medium size organisations (11 to 100 employees) have seen a significant increase from 2022 rates. This has been driven by a small number of organisations who have had disproportionate numbers of RIDDOR reportable accidents to their headcount.

Similarly, the trends highlighted in the 2022 AIR analysis, suggests that the organisations which are growing from owner operators or small practices into medium size organisations are more exposed to accidents, as their systems and processes are not as mature or are well established. In addition, the management and supervisory structure may not be as mature, and pressure could be placed on those within the organisations to get the job done.

As an industry development area, the availability of a stock geotechnical & geoenvironmental industry health and safety management system could aid in reducing risk within this area and support organisations through transition from small to a medium size business.

While AFRs do not indicate that medium size organisations have performed worse than in 2022, in fact a reduction in rates was recorded, they remain the group twice as likely to have accidents.

Both small and very large organisations have shown a significant reduction in accidents, and the most stable group size large, is showing a reduction from 2022, while maintaining consistency below industry average.

Industry Safety Culture

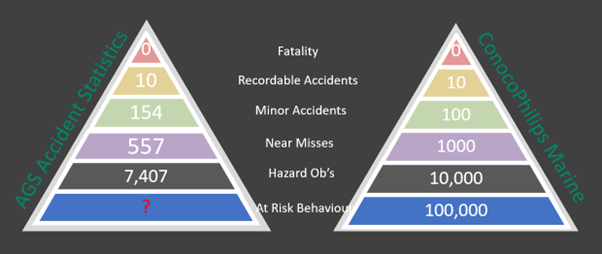

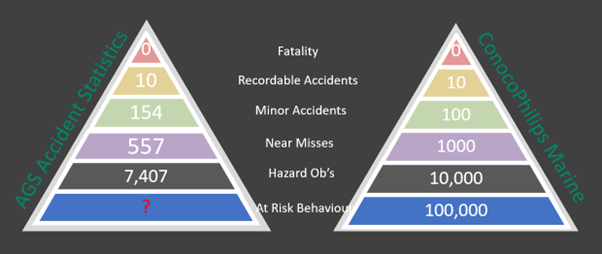

The ConocoPhilips Marine model has been used to measure culture, benchmarking the geotechnical & geoenvironmental industry accident incident data and ensuring uniformity with previous years accident incident statistics. This model placed the Safety Triangle within a modern occupational context and states that for every single fatality there are at least 30 lost workday cases, 300 minor injuries, 3,000 near misses (estimated), and 300,000 behaviours not consistent with proper safety procedures (estimated).

The industry culture looks weak around non-statutory reporting on comparison against this model, with Near Miss reporting 44% below model target. However, Hazard Spots at 74%, although under model target, represents a significant improvement on 2022 data. This can be a particularly hard area of improvement for organisations and an increase here does highlight cultural improvement.

Breaking down the data on Hazard Spots further, it’s clear that some organisations are performing better than others and are responsible for driving these rates up, however it’s a positive industry indicator within some less than positive industry accident statistics.

Summing Up

Although not submitted within our member accident data returns, I am aware of two fatalities reported within our industry in 2023. An owner operator lost their life while undertaking directional drilling, and a young engineer lost his life when they were struck by mobile plant. Both, considering the information which has been publicly released, were avoidable accidents which have resulted in family members not returning home at the end of the day.

Combined with the snapshot from the 42 AGS member organisations who shared their accident and incident data, 2023 is a year not to forget, rather it’s a year to remember and act upon.

This upward trend in significant accidents cannot go unchecked. Everyone working within the industry needs to review what they are doing, look what’s happening on the ground, what is being said in planning and client meetings and challenge unsafe conditions, unsafe planning, and unsafe behaviours. If an unsafe situation develops, we need to empower our people to challenge it.

As an industry we cannot keep sending our colleagues, friends, and family to work in situations where the risk of significant injury continues to increase. As an industry we must do better.

Article provided by Jon Rayner, AECOM SH&E Director